How Vascular Changes Alter the Brain: A Clear Guide to Vascular Dementia

A clinical, evidence-informed overview of what happens in the brain during vascular dementia — the vascular injuries, white-matter damage, inflammation, and network disruption that lead to cognitive decline — plus diagnosis, management, and prevention.

Introduction — why vascular health matters to the brain

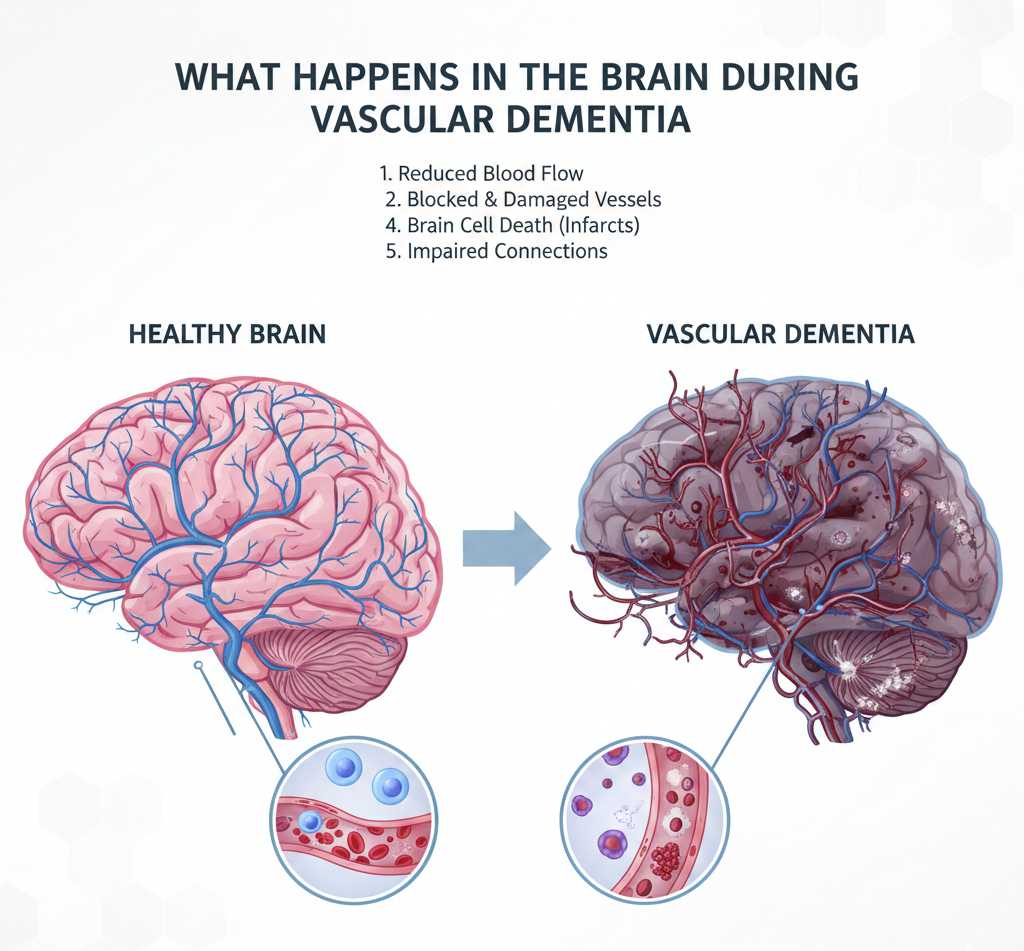

The brain depends on a constant, well-regulated blood supply. Oxygen and glucose arrive via cerebral blood flow; removal of waste and maintenance of the cellular environment depends on intact vessels and a healthy blood–brain barrier. When blood vessels are injured or narrowed, brain tissue suffers. Unlike single-cause neurodegenerative diseases, vascular dementia often reflects many small vascular insults added together — strokes, tiny infarcts, and chronic low-level ischemia — that gradually erode brain structure and function.

Basic brain anatomy related to blood supply

Understanding the vascular anatomy helps explain how damage produces cognitive symptoms:

- Large (macro) vessels: Carotid and vertebral arteries and their branches supply large brain territories. Blockage causes focal ischemic strokes.

- Small vessels (arterioles, capillaries): Penetrating arterioles supply deep brain structures and white matter. Small vessel disease damages these vessels and causes diffuse injury.

- Watershed zones: Areas between major arterial territories are vulnerable to low blood pressure and hypoperfusion.

- White matter tracts: Long-range axonal connections (e.g., corpus callosum, periventricular fibers) are metabolically vulnerable and rely on microvascular supply.

Key vascular processes that lead to brain injury

1) Large-vessel strokes (ischemic infarcts)

An occlusion in a major artery causes abrupt loss of blood flow to a cortical region. The result is necrosis of neurons and glia in that territory — a stroke. When strokes affect language, memory, or executive regions, they create stepwise declines in cognitive abilities. Recurrent strokes produce cumulative deficits.

2) Small vessel disease (SVD) and lacunar infarcts

SVD affects penetrating arterioles and capillaries. It produces tiny infarcts (lacunes), microbleeds, and progressive white-matter changes visible on MRI as white-matter hyperintensities (WMH). These diffuse injuries compromise long-range connectivity and slow information processing — a hallmark of vascular cognitive impairment.

3) Chronic hypoperfusion and watershed injury

Lowered cerebral perfusion — from heart failure, low blood pressure, or carotid disease — can cause selective vulnerability in watershed regions. Chronic low perfusion results in metabolic stress, demyelination, and axonal injury that impair network function.

4) Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA)

In older adults, amyloid protein can deposit in vessel walls (CAA), weakening them and increasing risk of microbleeds and lobar hemorrhage. CAA contributes to vascular injury and interacts with Alzheimer-type pathology in many patients.

5) Microhemorrhages and blood–brain barrier breakdown

Small vessel fragility can lead to microbleeds and leakage of plasma components into brain tissue. Breakdown of the blood–brain barrier triggers inflammation and interferes with neuronal function and repair.

What the tissue damage looks like — pathology and imaging

When clinicians or researchers examine the brain, vascular dementia is characterized by:

- Visible infarcts: Older cortical or subcortical strokes that leave cavitated areas.

- Lacunes: Small, round cavities in deep structures (basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule).

- Diffuse white-matter lesions (leukoaraiosis): Demyelination, gliosis, and axonal loss in periventricular and deep white matter.

- Microinfarcts and microbleeds: Microscopic lesions that accumulate and are only partly visible on standard imaging.

On MRI, typical signs include multiple infarcts, confluent white-matter hyperintensities on T2/FLAIR sequences, lacunar cavities, and susceptibility-weighted imaging showing microbleeds. PET and advanced MRI can show reduced perfusion and altered connectivity.

How vascular injury disrupts brain networks and cognition

The brain works through distributed networks — frontal–subcortical circuits, default mode network, language networks — that depend on intact white matter for efficient communication. Vascular injury disrupts these connections:

- Disconnection: White-matter lesions slow or block signal transmission, causing slowed processing speed, executive dysfunction, and attention deficits.

- Focal cortical loss: Strokes in specific regions produce focal deficits (e.g., aphasia, visuospatial loss) depending on location.

- Global network inefficiency: Microinfarcts and diffuse damage reduce the brain’s reserve, so small additional insults cause noticeable decline.

Clinically, vascular cognitive impairment often presents with slowed thinking, impaired planning and multitasking, stepwise progression, gait disturbance, urinary problems, and mood changes. Memory may be affected but often less prominently early on compared to Alzheimer disease.

Neuroinflammation and secondary injury

Vascular damage provokes an inflammatory response. Microglia and astrocytes become activated, cytokines rise, and oxidative stress increases. This environment impairs synaptic function and repair and can accelerate neurodegenerative processes. Chronic inflammation also promotes further vascular dysfunction — a vicious cycle.

Overlap with Alzheimer pathology — mixed dementia

Many older adults have both vascular lesions and Alzheimer-type changes (amyloid plaques, tau tangles). The coexistence — mixed dementia — is common and explains why clinical symptoms may include both memory loss typical of Alzheimer disease and the executive/processing slowing typical of vascular dementia. Treating vascular risk factors remains essential even when Alzheimer pathology is present.

How vascular dementia is diagnosed clinically

Diagnosis integrates clinical history, cognitive testing, and neuroimaging:

- History: Stepwise declines, recent strokes, vascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia), and gait or urinary changes raise suspicion.

- Neuropsychological testing: Highlights patterns such as slowed processing, executive dysfunction, and variable memory impairment.

- Brain imaging: MRI is preferred to detect infarcts, lacunes, white-matter hyperintensities, and microbleeds. CT can detect larger strokes and hemorrhages.

- Exclude reversible causes: Blood tests for thyroid disease, B12 deficiency, infections, and metabolic disturbances are important.

Several diagnostic criteria exist (e.g., NINDS-AIREN) for probable vascular dementia, combining cognitive impairment with evidence of cerebrovascular disease and a temporal relationship between vascular events and cognitive decline.

Current treatments and management strategies

There is no cure that reverses established vascular brain injury, but targeted interventions can slow progression, reduce new events, and improve quality of life.

1) Control vascular risk factors

- Manage hypertension (blood pressure control reduces stroke and white-matter progression).

- Tight glycemic control in diabetes.

- Lower LDL cholesterol where indicated.

- Smoking cessation and reduced alcohol intake.

- Promote exercise and healthy diet (e.g., Mediterranean-style diet).

2) Prevent recurrent stroke

Aspirin, anticoagulation when indicated (e.g., atrial fibrillation), carotid revascularization for significant stenosis, and management of cardiac sources of embolism reduce future infarcts.

3) Cognitive rehabilitation and supportive care

Therapies targeting executive function, practical compensatory strategies, occupational therapy, and caregiver support improve daily functioning and independence.

4) Symptom-directed medications

Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine — medications used in Alzheimer disease — have shown modest benefits in some vascular dementia patients, particularly when mixed pathology is present. Antidepressants may treat mood symptoms; gait disturbance may respond to physiotherapy.

Prevention — the most effective strategy

Primary prevention focuses on aggressive control of vascular risk across the lifespan:

- Early and sustained blood pressure control (single most important modifiable factor).

- Healthy lifestyle: physical activity, balanced diet, healthy weight.

- Smoking cessation and moderation of alcohol.

- Screening and treatment of atrial fibrillation and carotid disease when appropriate.

Prognosis and progression

Course varies widely. Some patients show stepwise declines after discrete events; others have slow, progressive impairment from chronic small-vessel disease. Mixed pathology often accelerates decline. Early detection and vascular risk control slow progression and reduce new injuries.

Emerging research and future directions

Active research seeks therapies to protect microvasculature, reduce neuroinflammation, clear microinfarcts, and enhance repair. Advanced imaging (high-field MRI, PET) and biomarkers (blood-based markers of vascular injury) aim to detect early disease before major cognitive decline. Trials of drugs that improve cerebral perfusion or target vascular pathology may offer new options in the coming years.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

A: Vascular dementia typically emphasizes slowed thinking and executive dysfunction from vascular injury and often has a stepwise pattern after strokes. Alzheimer disease primarily affects memory and a characteristic pattern of cortical degeneration. However, mixed pathology is common.

A: Established brain tissue loss from infarcts or chronic white-matter damage cannot be fully reversed. But progression can often be limited and cognition improved with rehabilitation and rigorous vascular risk management.

A: Brain MRI (to look for infarcts, lacunes, and white-matter disease), vascular imaging (carotid ultrasound/CTA), cardiac evaluation (ECG/echocardiogram), and blood tests to exclude reversible contributors are standard components of the workup.

A: Yes. Regular aerobic exercise, a heart-healthy diet, smoking cessation, good sleep, social engagement, and blood pressure control all reduce vascular risk and support brain health.

Practical next steps for patients and caregivers

- Discuss vascular risk assessment and brain imaging with your clinician if you have cognitive concerns or recent strokes.

- Work with primary care and specialists to optimize blood pressure, diabetes, lipids and cardiac rhythm.

- Ask for cognitive rehabilitation and practical supports (home safety, driving evaluation, caregiver resources).

- Plan for advance care preferences early — timely planning reduces stress later.